Space Invaders from Scratch - Part 3

In this series of posts, I am going to create a clone of the classic arcade game, space invaders, in C++ using only a few dependencies. In this post I will make the game loop run at a fixed time step, add the player and the aliens, and finally add sprite animation.

The complete code of this post can be found here.

Adding the Player and the Alien swarm

Before adding the player and aliens swarm, we create two data aggregates, i.e. structs,

struct Alien { size_t x, y; uint8_t type; }; struct Player { size_t x, y; size_t life; };

Both the player and alien structs have a position x, y given in pixels from the bottom left corner of the window. In the Player struct, we also include the number of lives of the player. In the classic space invaders arcade games, there are three alien types that differ only in their sprites. We encode this in the type field.

We also introduce a struct for all game related variables,

struct Game { size_t width, height; size_t num_aliens; Alien* aliens; Player player; };

this includes the width and height of the game in pixels, the player, and the aliens as a dynamically allocated array.

As we did previously, we add a sprite for the player, encoded as a bitmap.

Sprite player_sprite; player_sprite.width = 11; player_sprite.height = 7; player_sprite.data = new uint8_t[77] { 0,0,0,0,0,1,0,0,0,0,0, // .....@..... 0,0,0,0,1,1,1,0,0,0,0, // ....@@@.... 0,0,0,0,1,1,1,0,0,0,0, // ....@@@.... 0,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,0, // .@@@@@@@@@. 1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1, // @@@@@@@@@@@ 1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1, // @@@@@@@@@@@ 1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1, // @@@@@@@@@@@ };

We then create and initialize the Game struct,

Game game; game.width = buffer_width; game.height = buffer_height; game.num_aliens = 55; game.aliens = new Alien[game.num_aliens]; game.player.x = 112 - 5; game.player.y = 32; game.player.life = 3;

We set the number of aliens to 55, like in the original arcade game, give the player 3 lives, and set his position near the bottom center of the screen. We then proceed to initialize the alien positions to something reasonable,

for(size_t yi = 0; yi < 5; ++yi) { for(size_t xi = 0; xi < 11; ++xi) { game.aliens[yi * 11 + xi].x = 16 * xi + 20; game.aliens[yi * 11 + xi].y = 17 * yi + 128; } }

Finally, in the main loop, we draw the player and all aliens,

for(size_t ai = 0; ai < game.num_aliens; ++ai) { const Alien& alien = game.aliens[ai]; buffer_draw_sprite(&buffer, alien_sprite, alien.x, alien.y, rgb_to_uint32(128, 0, 0)); } buffer_draw_sprite(&buffer, player_sprite, game.player.x, game.player.y, rgb_to_uint32(128, 0, 0));

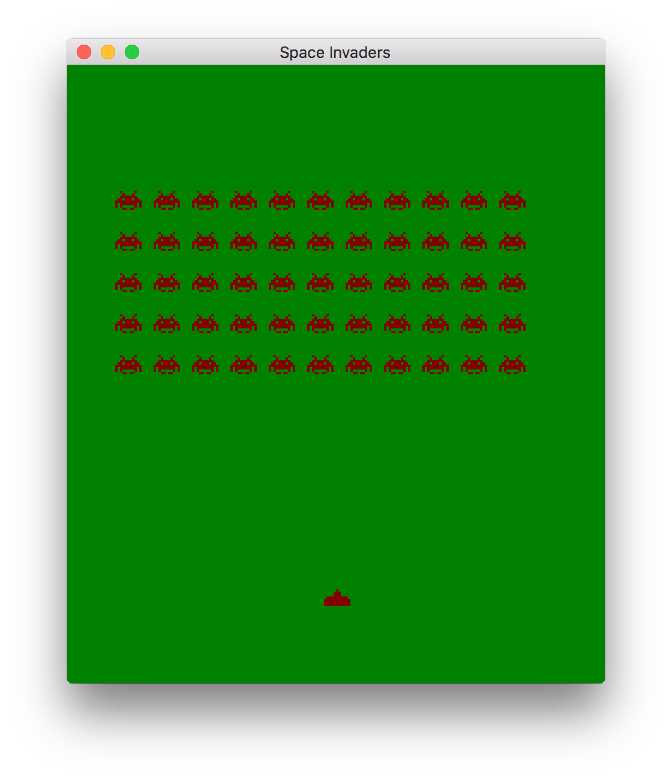

and here is the result,

This is already starting to look like space invaders, but it's quite static!

This is already starting to look like space invaders, but it's quite static!

Sprite Animation

To make the game more dynamic, we of course need to implement player input, but we also need some way to animate the sprites. The animation of sprites in video games is achieved by replacing the sprite with a series of sprites in succession. We thus create a data structure to hold various information about a sprite animation.

struct SpriteAnimation { bool loop; size_t num_frames; size_t frame_duration; size_t time; Sprite** frames; };

The SpriteAnimation struct is basically an array of Sprites. Here, we use a pointer-to-pointer type for the sprite storage so that sprites can be shared. If would like to be efficient, we could pack the sprites into spritesheets. In addition, we include a flag to tell us if we should loop over the animation or play it only once, the time between successive frames, and the time spent in the current animation instance. Given the number of frames and a desired duration of an animation, the time between successive frames can be easily calculated. Below, we introduce an additional sprite for our alien,

Sprite alien_sprite1; alien_sprite1.width = 11; alien_sprite1.height = 8; alien_sprite1.data = new uint8_t[88] { 0,0,1,0,0,0,0,0,1,0,0, // ..@.....@.. 1,0,0,1,0,0,0,1,0,0,1, // @..@...@..@ 1,0,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,0,1, // @.@@@@@@@.@ 1,1,1,0,1,1,1,0,1,1,1, // @@@.@@@.@@@ 1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1, // @@@@@@@@@@@ 0,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,0, // .@@@@@@@@@. 0,0,1,0,0,0,0,0,1,0,0, // ..@.....@.. 0,1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,1,0 // .@.......@. };

and create a two-frame animation using the two alien sprites,

SpriteAnimation* alien_animation = new SpriteAnimation; alien_animation->loop = true; alien_animation->num_frames = 2; alien_animation->frame_duration = 10; alien_animation->time = 0; alien_animation->frames = new Sprite*[2]; alien_animation->frames[0] = &alien_sprite0; alien_animation->frames[1] = &alien_sprite1;

Note that to make things easier, we measure the frame duration and time in game cycles, i.e. number of loop iterations. To make this work, we need to fix the frame rate. For a simple game like the one we are building, we can use V-sync, an option wherein video card updates are synchronized with the monitor refresh rate. Most modern monitors have a refresh rate of 60Hz, which means that the monitor is refreshed 60 times per second. Turning on V-sync will make our game a framerate of 60, or an integer multiple of the screen refresh. Unfortunately, this means that the game will run faster on monitors with a larger refresh rate, such as 120Hz or 240Hz monitors.

To turn V-sync on, we call the GLFW function glfwSwapInterval

glfwSwapInterval(1)

At the end of each frame, we update all animations by advancing the time. If an animation has reached its end, we either delete it, or set its time back to 0, if it is a looping animation.

++alien_animation->time; if(alien_animation->time == alien_animation->num_frames * alien_animation->frame_duration) { if(alien_animation->loop) alien_animation->time = 0; else { delete alien_animation; alien_animation = nullptr; } }

Note, that we currently only have one animation we need to update.

In the main loop where we draw the aliens, we update the drawing loop to draw the appropriate frame of the animation. The appropriate frame is calculated based on the time spent in the animation and the frame duration,

for(size_t ai = 0; ai < game.num_aliens; ++ai) { const Alien& alien = game.aliens[ai]; size_t current_frame = alien_animation->time / alien_animation->frame_duration; const Sprite& sprite = *alien_animation->frames[current_frame]; buffer_draw_sprite(&buffer, sprite, alien.x, alien.y, rgb_to_uint32(128, 0, 0)); }

To make things more interesting, we also add some arbitrary player movement, by introducing a variable that controls the player direction of movement,

int player_move_dir = 1;

and updating the player movement at the end of each frame based on it,

if(game.player.x + player_sprite.width + player_move_dir >= game.width - 1) { game.player.x = game.width - player_sprite.width - player_move_dir - 1; player_move_dir *= -1; } else if((int)game.player.x + player_move_dir <= 0) { game.player.x = 0; player_move_dir *= -1; } else game.player.x += player_move_dir;

The if conditions perform a basic collision detection of the player sprite with the game bounds, ensuring that the player stays within these bounds.

Above you can see an animated gif of the result.

Above you can see an animated gif of the result.

Conclusion

In this post, we set up some structs to logically group data for the game, the player, and the aliens. More importantly, we laid the groundwork for sprite animations. For this simple space invaders game, we assume a fixed clock which we set by turning V-sync on. This allows us to do sprite animation in game cycles instead of real time.

The only thing that is left before making the game playable, is the processing of user input. User input can come from various sources, but we will limit ourselves to the keyboard.